Off the keyboard of Gail Tverberg

Off the keyboard of Gail Tverberg

Follow us on Twitter @doomstead666

Friend us on Facebook

Published on the Our Finite World on March 29, 2016

Discuss this article at the Economics Table inside the Diner

Wage inequality is a topic in elections around the world. What can be done to provide more income for those without jobs, and those with low wages?

Wage inequality is really a sign of a deeper problem; basically it reflects an economic system that is not growing rapidly enough to satisfy everyone. In a finite world, it is easy for an economy to grow rapidly at first. In the early days, there are enough resources, such as land, fresh water, and metals, for each person to get a reasonable-sized amount. Each would-be farmer can obtain as much land as he thinks he can work with; fresh water is readily available virtually for free; and goods made with metals, such as cars, are not expensive. There are many jobs available, and wages for most people are fairly similar.

As population grows, and as resources degrade, the situation changes. It is still possible to grow enough food, but it takes large farms, with expensive equipment (but very few actual workers) to produce that food. It is possible to produce enough water, but it takes high-tech equipment and a handful of workers who know how to use the high-tech equipment. Metals suddenly need to be lighter and stronger and have other characteristics for the high tech industry, thus requiring more advanced products. International trade becomes more important to be able to get the correct mix of materials for the advanced products needed to operate the high-tech economy.

With these changes, the economic system that previously provided many jobs for those with limited training (often providing on-the-job training, if necessary) gradually became a system that provides a relatively small number of high-paying jobs, together with many low-paying jobs. In the United States, the change started happening in 1981, and has gotten worse recently.

Figure 1. Chart comparing income gains by the top 10% to those of the bottom 90%, by economist Emmanuel Saez. Based on an analysis of IRS data; published in Forbes.

What Happens When an Economy Doesn’t Grow Rapidly Enough?

If an economy is growing rapidly enough, it is easy for everyone to get close to an adequate amount. The way I think of the problem is that as economic growth slows, the “overhead” grows disproportionately, taking an ever-larger share of the goods and services the economy produces. The ordinary worker (non-supervisory worker, without advanced degrees) tends to get left out. Figure 2 is my representation of the problem, if the current pattern continues into the future.

Figure 2. Author’s depiction of changes to workers’ share of output of economy, if costs keep rising for other portions of the economy. (Chart is only intended to illustrate the problem; it is not based on a study of the relative amounts involved.)

Our economic growth system is reaching limits in a strange way

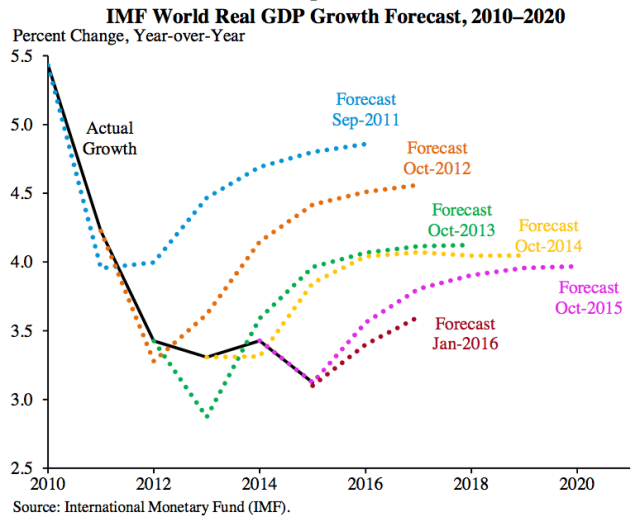

Economic growth never seems to be as high as those making forecasts would like it to be. This is a record of recent forecasts by the International Monetary Fund:

Figure 2 shows world economic growth on a different basis–a basis that appears to me to be very close to total world GDP, as measured in US dollars, without adjustment for inflation. On this basis, world GDP (or Gross Planetary Product as the author calls it) does very poorly in 2015, nearly as bad as in 2009.

Figure 2. Gross Planet Product at current prices (trillions of dollars) by Peter A. G. van Bergeijk in Voxeu, based on IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2015.

The poor 2015 performance in Figure 2 reflects a combination of falling inflation rates, as a result of falling commodity prices, and a rising relativity of the US dollar to other currencies.

Clearly something is wrong, but virtually no one has figured out the problem.

The World Energy System Is Reaching Limits in a Strange Double Way

We are experiencing a world economy that seems to be reaching limits, but the symptoms are not what peak oil groups warned about. Instead of high prices and lack of supply, we are facing indirect problems brought on by our high consumption of energy products. In my view, we have a double pump problem.

We don’t just extract fossil fuels. Instead, whether we intend to or not, we get a lot of other things as well: rising debt, rising pollution, and a more complex economy.

The system acts as if whenever one pump dispenses the energy products we want, another pump disperses other products we don’t want. Let’s look at three of the big unwanted “co-products.” Continue reading

Why Globalization Reaches Limits

We have been living in a world of rapid globalization, but this is not a condition that we can expect to continue indefinitely.

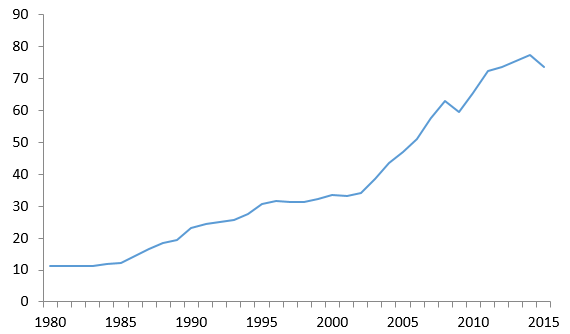

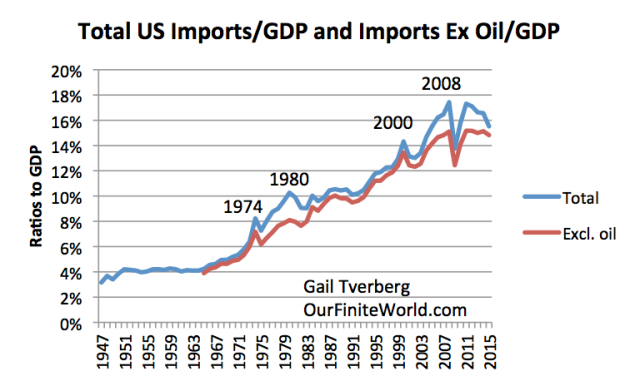

Each time imported goods and services start to surge as a percentage of GDP, these imports seem to be cut back, generally in a recession. The rising cost of the imports seems to have an adverse impact on the economy. (The imports I am showing are gross imports, rather than imports net of exports. I am using gross imports, because US exports tend to be of a different nature than US imports. US imports include many labor-intensive products, while exports tend to be goods such as agricultural goods and movie films that do not require much US labor.)

Recently, US imports seem to be down. Part of this reflects the impact of surging US oil production, and because of this, a declining need for oil imports. Figure 2 shows the impact of removing oil imports from the amounts shown on Figure 1.

Figure 2. Total US Imports of Goods and Services, and this total excluding crude oil imports, both as a ratio to GDP. Crude oil imports from https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/petr.pdf

The Physics of Energy and the Economy

I approach the subject of the physics of energy and the economy with some trepidation. An economy seems to be a dissipative system, but what does this really mean? There are not many people who understand dissipative systems, and very few who understand how an economy operates. The combination leads to an awfully lot of false beliefs about the energy needs of an economy.

The primary issue at hand is that, as a dissipative system, every economy has its own energy needs, just as every forest has its own energy needs (in terms of sunlight) and every plant and animal has its own energy needs, in one form or another. A hurricane is another dissipative system. It needs the energy it gets from warm ocean water. If it moves across land, it will soon weaken and die.

There is a fairly narrow range of acceptable energy levels–an animal without enough food weakens and is more likely to be eaten by a predator or to succumb to a disease. A plant without enough sunlight is likely to weaken and die.

In fact, the effects of not having enough energy flows may spread more widely than the individual plant or animal that weakens and dies. If the reason a plant dies is because the plant is part of a forest that over time has grown so dense that the plants in the understory cannot get enough light, then there may be a bigger problem. The dying plant material may accumulate to the point of encouraging forest fires. Such a forest fire may burn a fairly wide area of the forest. Thus, the indirect result may be to put to an end a portion of the forest ecosystem itself.

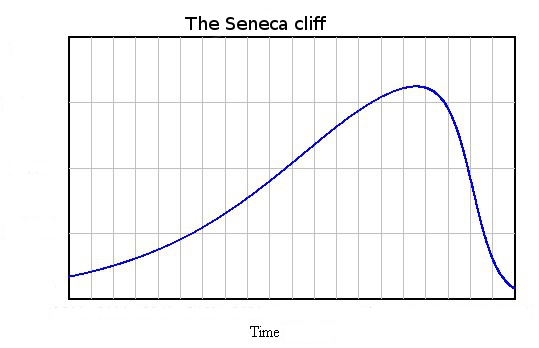

How should we expect an economy to behave over time? The pattern of energy dissipated over the life cycle of a dissipative system will vary, depending on the particular system. In the examples I gave, the pattern seems to somewhat follow what Ugo Bardi calls a Seneca Cliff.

The Seneca Cliff pattern is so-named because long ago, Lucius Seneca wrote:

It would be some consolation for the feebleness of our selves and our works if all things should perish as slowly as they come into being; but as it is, increases are of sluggish growth, but the way to ruin is rapid.

The Standard Wrong Belief about the Physics of Energy and the Economy

There is a standard wrong belief about the physics of energy and the economy; it is the belief we can somehow train the economy to get along without much energy. Continue reading

Why oil under $30 per barrel is a major problem

A person often reads that low oil prices–for example, $30 per barrel oil prices–will stimulate the economy, and the economy will soon bounce back. What is wrong with this story? A lot of things, as I see it:

1. Oil producers can’t really produce oil for $30 per barrel.

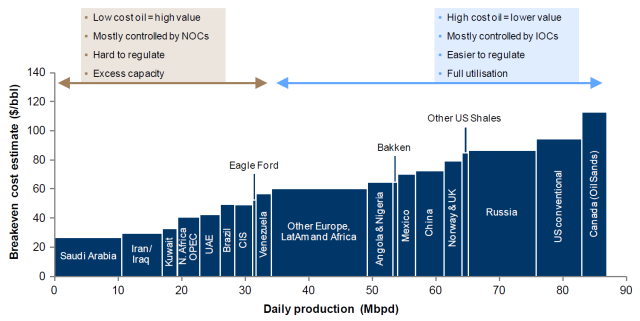

A few countries can get oil out of the ground for $30 per barrel. Figure 1 gives an approximation to technical extraction costs for various countries. Even on this basis, there aren’t many countries extracting oil for under $30 per barrel–only Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Iraq. We wouldn’t have much crude oil if only these countries produced oil.

Figure 1. Global breakeven prices (considering only technical extraction costs) versus production. Source: Alliance Bernstein, October 2014

2. Oil producers really need prices that are higher than the technical extraction costs shown in Figure 1, making the situation even worse.

Oil can only be extracted within a broader system. Companies need to pay taxes. These can be very high. Including these costs has historically brought total costs for many OPEC countries to over $100 per barrel.

Independent oil companies in non-OPEC countries also have costs other than technical extraction costs, including taxes and dividends to stockholders. Also, if companies are to avoid borrowing a huge amount of money, they need to have higher prices than simply the technical extraction costs. If they need to borrow, interest costs need to be considered as well.

3. When oil prices drop very low, producers generally don’t stop producing.